The Story

an adventure in five short sections

relating a journey of many years in which interesting metal objects are encountered

by Kevin Moreau, Blacksmith

In which I float small boats and big ideas

Drawing and building were my favorite ways to engage with the world as a child. My first love was boats, anything and everything to do with them. The kitchen sink was my tiny boatyard and a laboratory for experiments in flotation and displacement of water. I built model ships from kits, and later, scale models of small watercraft from scratch. I now understand that this is how I learn: hands-on, through experiment and observation.

In my teens, I developed a love for organ music, and the instruments themselves. I even wrote to an organ builder about an apprenticeship but learned that the company accepted applications only from those with master’s degrees in music. Musical notation in symbols? No, thank you! To this day, I can’t read a note, although I do explore organ music with my own set of keyboards, and I repair instruments, which reminds me to play.

Another gift from my childhood was an interest in history. My parents were avid readers and genealogists of our French Canadian ancestry, and they liked to drag me (willingly, I admit) to every historic site and tiny Roman Catholic cemetery within a day or two of our home in South Burlington, Vermont. My visits to various forts, battlefields, and historic buildings gave me a deep respect for the skill of anonymous tradespeople and the graceful and often whimsical design of everyday things.

In which I become a blacksmith

My work in metal began in my early 20s, when a boat designer counseled me to take shop courses at my old high school. I took his advice and learned some basic skills. He also said that blacksmithing was the most useful ancillary craft to woodworking and other trades because blacksmiths can make their own hand tools. This inspired me to try forging knives, by slow trial and error.

I met another amateur smith through a medieval reenactment group and was inspired to keep exploring bladesmithing. This was an exciting pursuit in 1980, when handmade knives were starting to become a thing. Soon, I abandoned boatbuilding and threw myself wholeheartedly into the craft of making blades. Through more trial and error, I taught myself how to make laminated (“Damascus”) steel and how to fit and finish metal and wood to increasingly high standards.

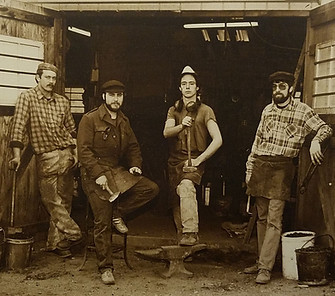

As my skills evolved, I sought employment in a blacksmithing shop and moved south to Brattleboro to work for Leigh Morrell. Production work and skilled colleagues challenged me in new ways, and blacksmithing elders like Bill Gichner stopped by for coffee and to talk about the trade. I worked for Leigh for six years while continuing to develop my bladesmithing skills. Then I went out on my own as a professional bladesmith and sword maker.

In which I try to escape the metal trades

As an independent bladesmith, I discovered two important things: business skills do not come easily to me, and while I admire skilled blade makers, I don’t have it in my heart to make instruments of brutal death and maiming. I quit blades, and after another round of production blacksmithing, I made the decision to leave the metal trades entirely. Lucky for me, it wasn’t that easy.

After a short stint as a dishwasher, I gained employment with the last great maker of wooden rowing shells, Graeme King. I enjoyed working with wood to create boats, but my experience with finely fitted metal components suited me to fit up the tubular stainless-steel outriggers for the oarlocks. So, in a shop renowned for its use of wood, I was the metal guy—and my metal skills increased.

Three years later, Graeme scaled back his business and laid off his assistants, so I was at a crossroads again. A close friend suggested that I “open a little blacksmith shop,” which seemed like a good idea, but I didn’t want to develop a production line of housewares. I needed my own specialty.

In which I discover locks & keys and consider their weight

I liked exploring flea markets in Southern Vermont, where I often found late-18th century keys and small locks. These mesmerized me. Here were wonderful little machines with removable pieces of art—the keys! I began researching pre-industrial locks and keys and developed new ways of using my metalworking skills to make them.

As a blacksmith, I loved the possibilities that locks and keys presented. There was no end to their variety, and there was room for both mechanical intricacy and artistic expression. The only limitation was my imagination.

I was also aware of the weight of these objects, both literal and figurative. I was drawn to their edginess and how they seemed to dare me to defeat them. I was troubled by the ways locks have been used against people, but handling them empowered me in a way that was different from bladed weapons, whose fundamental purpose is to cause harm. I love it when people engage with my locks and keys in a lighthearted way, and I’m delighted when people embrace them as symbols of their physical and psychological autonomy.

In which I inhabit an organ pipe casting shed, and many works are created

In 2001, I moved my shop from Townshend to Brattleboro and found that the only location that suited my purposes was the pipe-metal casting shed at the factory of the old Estey Organ Company. I’ve been there ever since, working around the long concrete slab where the Estey workers poured out metal alloy to roll into organ pipes.

In this phase of my career, I’ve established my mark, and all but the tiniest works are stamped with it. Many larger works are signed (Kevin P Moreau), and I’m meticulous about dating pieces whenever it’s physically possible. There are also works in the world with the stamp PFW for Plumb Farm Workshops, my earlier business name.

Throughout this time, great people in the lock-collecting community have embraced my work and shared my enthusiasm for these fascinating objects. I’ve studied antiques, which is like shaking hands with their makers. And on the weekends in the warm months, I sometimes hear music from my neighbors at the Estey Organ Museum across the way.

Epilogue: In which I look toward the future

Any independent artisan will tell you that working for yourself is not a stress-free job. Living indoors is nothing I take for granted. But I’ve been lucky to sustain a spirit of fun in my work, and I’ve been able to guide and encourage others to develop their own skills in metal. My work space is tricky for formal instruction, but I have learned how to look, draw, experiment, and find confidence in the creative life, and I welcome opportunities to pass along what I’ve discovered.

–Kevin Moreau, 2025